Part 1

The second of April 2025 will certainly go down in the history books. The “Liberation day” announced by Donald Trump has resulted in the introduction of new tariffs that we have not seen for a very long time, nearly 100 years, and which largely triggered the world economic crisis of 1929-1933. In the month and a half since the beginning of April, it has become clear that Trump’s ‘art of the deal’ style of politics is all about opening up with something huge, surprising, much, then pressuring your opponent and finally agreeing with him for a fraction of the original levels, which is ultimately seen as a victory by the opponent. But are the tariffs against all countries – allies and enemies – or just against a particular competitor? It is now abundantly clear that the main target of the tariffs is China, and Trump is willing to do anything to break China’s economic power and break his country’s economic dependence on China.

- The situation in China

China, the world’s second most populous country, owes its former glory to significant economic growth, with a growth rate well above 5%. Of course, this started from a low base, but one thing is certain: the growth of the economy has been felt by the population and has been an important component of its financial recovery. Economic growth has basically rested on three pillars: construction and real estate, relatively cheap labour market, and export activities.

Let’s look at these in turn:

With economic growth of 7-9% per year since the early 2000s, the population has moved to the big cities, where there were significant new job opportunities. Megacities were created and the huge influx of workers from the countryside needed somewhere to live. Huge housing estates began to be built, for which there was a huge demand. This, backed up by soft loans, eventually created a huge housing boom. Property prices rose for a decade, and for many people moving to the big city, property became the only asset they had, bought mainly on credit. Meanwhile, GDP growth has fallen to around 5%, but if the housing bubble will burst, many developers and lending banks could fail and the public could cut back on consumption, further reducing economic growth.

So the government has decided to try to deflate the bubble slowly, introducing the ‘three red lines’ of debt regulation in 2020 to limit new corporate borrowing, cooling the housing market. Its aim is to ensure that homes are bought for use, not speculation. This measure has caused serious difficulties for some property developers. One of the largest developers, Evergrande, went bankrupt in November 2021. As a result of the restrictions, the bubble has started to deflate, with house prices falling by 4-6% a year. At the same time, the number of uncompleted unsold homes is estimated to remain close to 65-80 million.

The government has cut interest rates, giving debtors breathing space. It is hoped that this measure will generate additional consumption by households from the amount left over from loan repayments.

But it is difficult to change the consumption habits of the Chinese: we are talking about a society that traditionally consumes little. The propensity to save is high, with more than 40% of GDP spent on savings and investment. What they do not consume, they are forced to export. They export to a country that is a primary consumer: the US.

To help the effect of these exports a little, the government is gradually weakening the yuan, which will help them maintain their high export capacity.

2. The situation in the USA

While China’s problem is that its consumption is too low and its savings too high (hence its economy’s growth rate is falling), the US is in the opposite situation: its consumption is too high and its savings too low (hence it is heavily indebted).

While China is forced to export, the US wants to import. This could be a perfectly good equilibrium. However, the US has financed its trade deficit due to import surplus by increasing its debt.

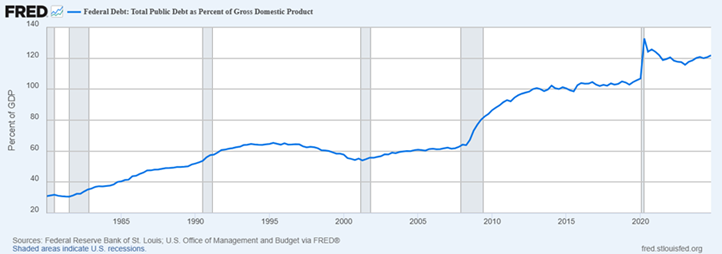

Its debt-to-GDP ratio more than doubled from 2001 to 2025, from 56% to close to 124%.

Moreover, with the increased interest burden, this debt is growing, and the question of how to stop it is becoming more and more pressing. Even though debt ceiling rules have been introduced in vain, the Senate has no choice – although there is always political debate around it – but to finally agree to raise the debt ceiling. It has become a political issue, not a real solution to the economic problems.

Let’s look at how it came about and what factors have accelerated the rise in debt levels:

1. Company level

During the Second World War, the US was the only country that did not suffer significant war damage, but at the end of the war almost all countries were left in debt. You could say that the real winner of the Second World War was the USA. In economic terms, certainly. The Cold War saw the emergence of a capitalist approach to corporate governance, which sought to exploit the efficient running of companies, the financial reward of workers and the real positive social effects of competitive advantage. Profit was important, but not at all costs. For this reason, although capitalists benefited more than workers, the difference was not so great that both classes valued the gains positively, and the American dream was realised.

However, the economic boom also meant that the savings of the population grew and had to be invested. Thus, while after the Second World War the stock market was only a playground for capitalists, from the 1980s there was a growing demand from the middle class to invest: money market funds, then equity market funds, then electronic trading, then ETFs. The primary objective became to maximise corporate profits, while the efficient management of companies and the maintenance of the common good became secondary. Everything was subordinated to the goal of posting a slightly higher profit quarter after quarter.

In order to achieve high profits, costs had to be driven down, so production was relocated to cheaper countries, especially Asia. In the USA, increased prosperity meant that these jobs were no longer done or were very expensive (e.g. textiles), while in China, every job opportunity was seized because it was seen as the basis for social uplift. American companies that did not need skilled labour force could maximise profits – and meet stock market expectations – by outsourcing the work and then re-importing the finished product. The result is a system of relations between the two countries in which China produces and the US consumes. In this system, developing countries prefer to save at cheap prices, working hard, in the hope of rising, while developed countries (e.g. the US) prefer to consume, even beyond their means, on credit, because that is what wealth means to them. After the bursting of the tech bubble in 2001, this process accelerated and has been steady over the last 20 years.

2. Individual level

The American consumer and the Chinese producer are very different in economic terms. The American consumer measures his or her well-being by having ready access to a wide range of goods and services, with a huge choice and competing prices for each product. It is perfectly natural for him to find products that are hardly different from each other lined up on the shelves at Walmart, and he spends hours for shopping. His average hourly wage is $36, but when he runs out of money, he spends it on credit, and when he sees a sale, he gets the products through a BNPL (buy now pay later) provider. The savings rate of the US population is just 15%, meaning that only 15 out of every $100 is spent on savings.

In contrast, his Chinese counterpart robots along a production line at an average hourly wage of $3.7, a tenth of his US counterpart. On this small income, he consumes little and saves a significant amount, nearly 40% of their income. The only way to get ahead is to earn an income from work, to be willing to save. Based on its historical traditions, it is subject to social and cultural influences quite different from those of the average American.

3. National economic level

For the reasons described above, consumption now accounts for more than 70% of US GDP. Thus, if consumption stops or declines, the chances of recession increase, and therefore the level of consumption must be maintained. As an experiment, the first way they dealt with the crisis in 2008 was to simply print money and give it to the population in various forms, which they then started to buy. The additional demand boosted consumption, which saved the corporate sector and then the capital markets. Then, in the Covid crisis, came the real liquidity bonanza: paychecks were repeatedly handed out to citizens, who also bought, and there was no shortage of V-shaped stock market recovery. They seemed to have found the solution: in any economic downturn, printing money and stimulating consumption would solve the problem.

Although everyone thought this money pump would eventually cause inflation, it didn’t. The question is why not? The reason is now clear: the „world money status” of the dollar and the constant demand for the greenback. Why this has led to the rise of China and what solutions are possible will be discussed in the second part of this article, coming soon…